Argumentation skills

Background

As part of 2digi2, we conducted a survey that asked language center teachers about argumentation. No single approach to teaching argumentation was found to be the most popular. There are no doubt cultural, language and field-specific differences that create a variety of approaches, and this variety is likely a sign of the great variety of topics and approaches language and communications teachers face in their work.

Argumentation is of course central to critical thinking. We asked researcher Tuukka Tomperi what language center teachers should know about critical thinking in general and how they should apply what they know in their teaching. The good news is that when we teach language and communication skills, we automatically engage our critical thinking skills.

Listen to Tuukka’s interview 26:10 min). Note: the interview is in Finnish, with an English transcription available.

Haastattelussa Tuukka Tomperi – transkripti

0:01

Tommi Kakko: Tuukka Tomperi on tutkija, Tampereen yliopiston kasvatustieteiden tiedekunnasta, tiedetoimittaja oppija tietokirjailija.

0:12

Lupauduit, Tuukka, ystävällisesti kertomaan meille kielikeskusopettajille jotain kriittisestä ajattelusta. Ennen kuin tehdään ihan mitä muuta, niin voitko antaa meille määritelmän kriittisestä ajattelusta?

0:26

Tuukka Tomperi: Joo kiitoksia, Tommi. On oikein mukava osallistua tähän ja aihehan on tosiaan laaja erittäin tärkeä mulle, hyvin läheinen siinä mielessä että mä oon alkuperäiseltä koulutukseltani filosofi. Mä en tiedä miksi mä kutsuisin nykyään, mutta opettajankoulutuksen ja kasvatustieteiden puolella on ollut kaksituhattaluvun töissä ja tän kriittisen ajattelun opettaminen ja se mitenkä opettajat voi opettaa kriittistä ajattelua eli ne pedagogiset lähtökohdat kriittisen ajattelun opettamiseen ollut mulle nimenomaan semmoinen aihe mitä mä oon koittanut

0:58

tutkii ja josta kirjoittanut ja sitten josta olen opettanut. Joten eiköhän me tästä jotain selkoa saada tässä keskustelussa. Tietysti ensin saattaa herätä kysymys, että mitä se kriittinen ajattelu sitten on ja monesti se arkikielessä ja mediassakin yhdistetään tällaiseen torjuntaan ja kielteisyyteen tämä kriittisyys, mutta silloin me puhutaan tieteessä ja filosofiassa ja psykologiassa ja kasvatuksessa siitä, että mitä on kriittinen ajattelu ja siihen opettaminen tai kasvattaminen, niin niin silloin viitataan ihan tietyllä tavalla.

1:31

nimenomaan niinku harkintakykyyn ja arviointikykyyn eli siihen, että kyseenalaistetaan meidän uskomuksia sekä omia uskomuksia että toisten esittämiä uskomuksia. Kyseenalaistetaan meidän maailmankuvaa käsityksiä arvoja tutkitaan niitä perusteellisesti, jotta me kyetään harkitsemaan, että ollaanko me oikeassa vai väärässä. Ja siinä on sen kriittisen ajattelun ydin: että me pidättäydytään ensin ottamasta mielipidettä tai esittämästä jotain arvosteltavaa sen verran paljon, että me pystytään muodostamaan tarkempi kuva

2:05

siitä asiasta, mitä mistä meidän pitäisi olla jotain mieltä ja sitten vasta muodostetaan ikään kuin tämmöinen arvostelukykyinen käsitys siitä aiheesta ja sitä on monella tavalla määritelty, että mitä kriittinen ajattelu sitten on. Mutta yksi yksi mitä mä oon käyttänyt paljon semmoisen filosofin kuin Matthew Lipmanin määritelmä kuuluu näin, että kriittinen ajattelija ajattelee rationaalisena tavalla, joka edistää arvostelukykyä, tukeutuu kriteereihin, on itseään korjaavaa

2:36

sekä kontekstitietoista. Tää on vähän kompleksinen, mutta kaikki noi perusasiat tulee siinä kuitenkin mukaan: että pitää soveltaa jotakin yhteismitallisia kriteereitä, kun me arvioidaan jotakin asiaa, pitää ottaa konteksti, elikkä se tietosisältö se tietoalueen huomioon muuten kriittinen ajattelu ei onnistu. Ellei me tiedetä siitä asiasta paljon, pitää kyetä korjaamaan omia käsityksiäni, eli pitää ottaa huomioon, että me voidaan olla erehtyväisiä. Siitä kaikki kriittinen ajattelu aina lähtee ja sitten pyritään

3:07

järkiperäisesti elikkä rationaalisesti tällä tavoin kehittämään omia omaa kykyämme, arvioida asioita ja ilmiöitä eli tutkivaa ajattelua, joka kyseenalaistaa uskomuksia. On kriittinen ajattelu pohjimmiltaan.

3:23

Tommi: OK entäs sitten kielikeskusopettajat? Mitä nimenomaan meidän pitäisi tietää kriittisestä ajattelusta?

3:31

Tuukka: Jos mä nyt ajattelen sitten nimenomaan, siis viestinnän opetusta ja kielten opetusta ja kielikeskusopettajien työtä.

3:40

Niin mun mielestä siis,

3:42

voin sanoa

3:43

heti kärkeen että nää kulkee aivan käsi kädessä. Eli te olette jo nyt siellä ihan asian ytimessä. Se on ehkä mun pääsanoma: ettei tarvitse miettiä mitään ihmeellisiä kommervenkkejä. Jos te teette perustyötänne hyvin, niin se on aivan keskeinen osa kriittisen ajattelun opettamista yliopisto-opiskelijoille, ja tää kaikki lähtee tietysti siitä, että me tiedetään psykologisesti, että kaikki kehittyneempi korkeatasoisempi ajattelu eli kaikki käsitteellinen ajattelu, niin sehän tapahtuu kielessä.

4:15

Se käyttää kieltä, ja kieli ja ajattelu on käsi kädessä silloin kun me pyritään ajattelemaan hyvin jotakin sisällöllisiä aiheita. Se ei onnistu ilman kieltä ja tota tämmöinen

4:28

uudempi sosiokonstruktiivinen oppimispsykologi (termillä ei sinänsä nyt ole väliä, mutta sanotaan, että uudempi oppimispsykologia), jonka keskeinen pioneeri oli venäläinen Lev Vygotsky. Niin sehän toi meidän käsityksiin tietoisuuden siitä, että me ihmiset opimme korkeatasoista tai käsitteellistä ajattelua nimenomaan osallistumalla kommunikaatioon. Eli ajattelun oppiminen esimerkiksi lasten kohdalla tapahtuu niin, että he pääsevät keskustelemaan ja seuraamaan toisten ihmisten keskustelua.

5:01

Ja vähitellen he siis sisäistävät niitä kommunikaatiossa esiintyviä piirteitä ja keinoja ja taitoja omaan ajatteluun niin, että he voivat tehdä sen päänsä sisällään tai missä sitten ajattelu tapahtuukaan niin kaikessa hiljaisuudessa ilman kommunikointia. Mutta kieli ja osallistuminen taitavasti ajattelevan ja keskustelevaan kieliyhteisöön on juuri se reitti, millä me opimme taitavaa ajattelua eli tässä mielessä jo lähtökohtaisesti kielten kielitaitojen,

5:32

kielellisten kykyjen ja valmiuksien opettaminen on nimenomaan sitä, että opetetaan ajattelun taitoja. Samalla

5:41

tähän lisäyksenä nykypäivään katsoen, jos mietitään sitä, että mitä mitä kommunikaatio ja kriittinen ajattelu tänä päivänä

5:51

itselleni tuo mieleen, niin siinä korostuu se, että voisi sanoa, että meidän nykyisen kulttuurin ja yhteiskunnan piirteiden vuoksi

6:01

kriittinen ajattelu on yhä enemmän mediakritiikkiä. Eli me tarvitaan yhä enemmän tämmöisiä tulkinnallisia kriittisiä mediataitoja ja valmiuksia, joita ilman me ei pystytä sellaiseen älylliseen itsepuolustukseen. Mitä kriittinen ajattelu on ja mitä sen on tarkoitus olla? Me eletään tällä hetkellä yhteiskunnassa tai kulttuurissa tai maailmassa missä

6:23

meillä on enemmän ja parempia mahdollisuuksia tietoperäiseen ajatteluun ja viestintään kuin koskaan aikaisemmin ihmiskunnan historiassa. Mutta samaan aikaan siihen sisältyy myös valtavasti hälyä mis- ja disinformaatiota, kuten kaikki tiedätte. Kaikki nää ongelmat on yhtä laajoja kuin ne mahdollisuudet mitä se teknologia viestinnässä ja mediassa ja digimediassa sisältää. Eli vaikka näitä periaatteellisia mahdollisuuksia

6:54

tietoperäisen ja hyvin ajattelevan yhteiskunnan kehittämisen on enemmän kuin koskaan, niin se sama seikka kuin ennenkin pitää paikkansa: että tietämys tai tieto vaikuttaa yhteiskuntaan. Ne tekee maailmaa paremmaksi tai tota antaa meille mahdollisuudet parantaa maailmaa ainoastaan siinä tapauksessa, että sitä tietoa kyetään muuttamaan

7:15

tällaiseksi, yksilölliseksi ja yhteisölliseksi tietämyksesi, joka on jollakin tavalla käytännöllistä, ja jos me ei kyetä hyödyntämään sitä tietoa kriittisesti ja taitavasti yksi toistemme kanssa, niin silloin se tiedon määrä ja saatavilla olo ei auta meitä loppujen lopuksi yhtään mitään.

7:35

Ja mediakritiikki, jos tänä päivänä ajattelee, niin se on helppo huomata, että siellä on monia semmoisia tekijöitä mitkä on hyvin haasteellisia meidän ajattelulle: jatkuvasti on liikaa informaatiota, enemmän kuin me kyetään sulattamaan ihan mistä tahansa aiheesta. Joka päivä on täynnä sellaista materiaalia, että me ei mitenkään voida seurata kaikkea sitä mitä me voitaisiin kuvitella seuraavamme.

7:59

Ja sitten, koska sitä informaatiota on niin paljon, niin asiat ei kytkeydy toisiinsa, eli syntyy tällaista merkitysvajetta, jota me täytetään tavallaan aikaisemman tiedon pohjalla tai aikaisempien ennakkoluulojen pohjalla tai omien kokemusten tai tunteiden tai minkä tahansa tämmöisiä helpommin tartuntatavan pohjalta. Eli meillä me ei pystytä luomaan riittävästi linkkejä asioiden välillä, että me ymmärrettäisi niitä ihan täydellisesti. No sitten ei tietenkään ole nimenomaan riittävästi sitä aikaa ajatella pysähtyä kyseenalaistamaan

8:29

kaikkia uutisia tai kaikkia mediasisältöjä, kaikkia somekeskusteluja, mitä me kohdataan, ne menee tommoisena virtaavan nauhana meidän silmien ohitse ja hyvin harvoin me loppujen lopuksi pystytään keskittymällä oikein kunnolla pysähtymään. Eli meillä puuttuu jatkuvasti aikaa ja sitten lisäksi ihmisten muisti on tietysti aina rajallinen. Vaikka me oltaisiin opittu monia asioita vuosien tai vuosikymmenten varrella, niin kyllä ne tuppaa painumaan sinne muistin hämäriin, ettei me pystytä palauttamaan niitä mieleemme.

9:00

Eli tässä tämmöisessä niinku äärimmäisen saturoituneessa vilkkaassa mediaympäristössä toimiminen on meidän kaltaisille olennoille, joiden psykologiset valmiudet ei ole ihan hirveästi kuitenkaan muuttuneet kymmenien tuhansien vuosien aikana on hyvin hankalaa ja tää tuo

9:19

meille eteen just sen kysymyksen, että nyt tämmöisessä yhteiskunnassa voisi ajatella, että meillä kriittisen ajattelun tarve on suurempi kuin koskaan juuri siitä syystä, että me eletään tällaisessa viestintäympäristössä, joka on näin täynnä kaikennäköistä yritystä vaikuttaa meihin.

9:39

Mutta edelleen se pääsanoma teille viestinnän ja kielten ja kielen taitojen opettajille on juuri se, että silloin kun opiskelijoita opetetaan kommunikoimaan hyvin

9:53

huolellisesti, harkitusti, jäsentyneen selkeästi ja sitten vastaavasti myös lukemaan ja kuuntelemaan hyvin ja huolellisesti toisten viestintää, niin nää on jo nykyisen kriittisen ajattelun kannalta aivan ydinasioita. Eli tässä mielessä mä näen viestinnän opettamisen kaikissa muodoissaan

10:15

olevan aivan keskeinen osa kriittisen ajattelun opettamista ilman mitään sen kummempia kommervenkkejä, joita toki voi myös sitten myös osaltaan miettiä, mutta ne ei tietenkään ole asian ydin.

Tommi: Yksi sellainen lähestymistapa informaatioon, mikä on ihan uusi juttu tekoälyn ja muun sen sellaisen kanssa:

10:42

se ei ole pelkästään ongelmanlähde, vaan sieltä löytyy myös apuvälineitä, joilla sitten jotenkin

10:50

suodattaa tietoa ja jäsenellä sitä. Niin onko sulla mitään sellaista

10:57

visiota tai näkemystä tai jotain tuntumaa siihen, että millä tavalla digitaaliset työkalut sitten voi (sen sijaan että että ne olisi

11:11

pelkkä ongelma) olla myös hyödyksi. Mulla on pyörii päässä sellainen joku extended mind -tyyppinen ajattelu, missä nää työvälineet auttaa, kun oma muisti loppuu. Joku digitaalinen apulainen, joka hoitaa asioita sun puolesta.

Tuukka: No se on erittäin tässä päivässä tärkeä kysymys ja se on nimenomaan juuri näin

11:36

tästä minkä sä mainitsit extended mindin, laajennetun mielen tai jopa laajennetun tietoisuuden tutkimuksen näkökulmasta, niin näähän on olleet ne erilaiset välineet. Kaikki oikeastaan kommunikaation ja muistiin merkitsemisen välineet, jo niinku kirjallinen teksti ja kuvat ja kaikki tätä ennen painettu ilmaisu, on ollut meidän mielemme laajentumisia. Ne on ollut ennen kaikkea monesta tapauksessa meidän muistimme laajentumisia, että meidän ei tarvitse esimerkiksi opetella muistamaan

12:08

kuvatarkasti jotakin karttaa mielessämme, kun me voidaan katsoa sitä karttaa paperilta tai nykyään kännykästä.

12:15

Ja se, että nää digitaaliset välineet on kehittyneet niin nopeasti viime vuosikymmeninä, se on tuonut tietysti valtavasti mahdollisuuksia lisää meille. Se on tänä päivänä kaikille meille oikeastaan opettajillekin selvää, että ne on kaikkein tärkein apuväline meidän ajattelulle ja muistille. Mutta jos mä käytän tota karttaa esimerkkiä nyt hiukan, niin siitä tulee mieleen tämmöinen tämmöinen puoli, että

12:41

digiteknologia saattaa myös jollakin tavalla kaventaa meidän ajattelua. Ja nyt mä tarkoitan tällä sitä, että jos mä ajattelen karttaa, joka on paperilla ja karttaa jota nykyään käytetään vaikka kännykän kautta, niin ennen kun me käytettiin sitä karttaa paperilta, niin tietysti

13:02

jos me oltiin huonojen maamerkkien varassa tai ilman kadunnimiä, niin me tarvittiin vielä kompassia siihen. Lisäksi meidän piti sijoittaa itsemme jotenkin sille kartalle ja opetella lukemaan sitä kompassia ja karttaa (se on aika vaativa taito loppujen lopuksi) ja tunnistamaan niitä kohteita kartalla. No OK, tää nykyihmisten, urbaanien ihmisten niinku minunkin kartanlukutaito on perustunut vaan siihen, että katsotaan kadun nimiä ja rakennuksia, sitten suuntaudutaan siellä kartalla. Nyt tän digiteknologian aikana niin on itse asiassa niin, että mehän voidaan lyödä sieltä vaan se reitti

13:34

päälle ja sen jälkeen kuunnellaan opasteita tai katsoa niitä: käänny vasemmalle, käänny oikealle, jatka suoraan. Meidän ei tarvitse edes oppia lukemaan sitä karttaa, jolloinka siitä katoaa ymmärrys siitä missä me ollaan sillä kartalla. Mä näen että tää on hyvä esimerkki siitä, että miten nämä tehokkaat teknologiat voi tuottaa myös monenlaisia haittoja tai supistaa kaventaa meidän ajatteluamme ja rajoittaa meidän ymmärrystämme. Juuri tää riski niissä kaikissa on olemassa.

14:05

Ja nämä näkyy ehkä parhaiten.

14:08

nämä digiteknologiariskit nimenomaan tämän niin sanotun tekoälyn kehittymisessä. Me ollaan kaikki huomattu, että vaikka sosiaalinen media on täynnä innostuneisuutta siitä, että mitä kaikkea voi saada aikaan näillä tekoälyohjelmistoilla tai sovelluksilla ja siinä niinku etenkin ehkä nuoremmilta sukupolvilta saattaa

14:30

unohtuu se (ja toki vanhemmiltakin jos ei ole perehtynyt asiaan), että ei nää ole itse asiassa minkäänlaisia älyjä. Nää ei ole tekoälyjä, jotka vertautuu älykkyyteen inhimillisessä mielessä. Ne on konelaskentaa,

14:44

joka perustuu tiettyihin algoritmeihin ja sitten tiettyyn datamäärän, jota ne algoritmit seuloo ja sitten komentokehotteen prompteilla ne tuottaa sen pohjalta meille jonkinnäköisiä vastauksia tai sisältöjä. Juuri tämä, että ne ei itse asiassa ole älykkäitä eikä etenkään ajattele yhtään mitään, se tuo vastaan sitten oikeastaan sen havainnon, että se ajattelun työ ja vaiva jää

15:16

edelleen meille ihmisille. Ja mitä enemmän tää datateknologia lisääntyy ja mitä enemmän se muodostaa tämmöisen mustan laatikon,

15:28

millä mä tarkoitan sitä, että me ei enää ymmärretä, mitä sen sisällä tapahtuu samassa mielessä, kuin jos me jos me suunnistetaan karttasovelluksen avulla ainoastaan niin, että me kuullaan sieltä että ”mene tuonne” ja ”mene tuonne”, niin me ei enää tiedetä, mitä siinä kartassa itse asiassa tapahtuu. Me ei tiedetä, missä me mennään. Se on ikään kuin meille musta laatikko, josta me saadaan vaan output. Mitä enemmän se on tän tyyppistä, että se kätkeytyy meiltä että miten teknologia toimii, niin sen korostuneemmaksi tulee se tarve

15:58

ymmärtää paremmin se teknologia, jotta me voidaan ajatella sen kanssa ja myös siitä kriittisesti. Ne apuvälineet on ehdottomasti tehokkaita. Esimerkiksi internet erilaisina informaatiosisältöineen, niin sehän on ollut valtavan vapauttavaa, koska

16:15

meille riittää tietyntyyppinen metatieto myös monista asioista. Jos me tiedetään, että mistä me haetaan yksityiskohtainen tieto, vuosiluvut tai nimet tai jotkut tällaiset jutut, niitä ei tarvitse painaa muistiin. Mutta edelleen me tarvitaan sitä metatietoa. Elikkä me tarvitaan edelleen sen tietoalueen kokonaisvaltainen ymmärrys, ja paljon meidän pitää oppia myös niitä tietosisältöjä. Muuten me ei pystytä käyttämään internetiä tehokkaasti. Ja samalla tavalla minkä tahansa uuden teknologian kanssa: meidän pitäisi opetella kuitenkin ymmärtämään, että miten se teknologia toimii,

16:47

jotta me voidaan suhtautua siihen kriittisesti ja jotta me voidaan käyttää kriittisesti sitä tehokkaana apuna omana omalle ajattelulle.

16:57

Ja nyt jos mä ajattelen, että miten opettajat kohtaa tän uuden teknologian ja vaikkapa nyt tän konelaskennan eli tekoälyn teknologian, niin mä itse koitan opettajillekin aina sanoa, että meidän on koetettava pysyä perillä ja perässä siinä kehityksessä siinä mitassa, että me ymmärretään, mitä tapahtuu ja me ymmärretään mitä ne uudet teknologiat tekee ja mitä niillä voi tehdä. Eli nyt esimerkiksi tällä hetkellä, miten joku ChatGPT tuottaa tekstiä. On hyvä

17:29

tutustua siihen periaatteeseen, koska se on eräänlainen arvausteknologia ennakointiteknologia. Mitään sisältöä siellä ei itsessään ole, minkä se ikään kuin ajatellen meille tuottaisi. Mutta on hyvä tietää, että miten se toimii, jotta me ymmärretään mitä siinä tapahtuu ja jotta me pystytään myös opettamaan opiskelijoita suhtautumaan siihen kriittisesti ja riittävällä tavalla ymmärtäen minkälaisia riskejä niihin sisältyy. Jos me pudotaan teknologian kyydistä, niin silloin me ei enää huomata niitä

18:00

kriittisen ajattelun tarpeita eikä pystytä haastamaan myöskään opiskelijoita suhtautumaan uuteen teknologiaan kriittisesti. Samalla tavalla kuin (jos nyt karrikoisi historian valossa) ajattelisi, että siihen vanhaan suusanallisesti yliopiston perinteeseen kasvanut opettaja yhtäkkiä kohtaa tilanteen, missä kirjapainotaito on yleistynyt ja opiskelijat itse voi jopa ostaa ihan kirjoja lukea niitä omalla ajallaan. Niin siis jos ei hän ymmärrä tämän merkitystä, niin silloin hän putoaa kyydistä, eikä tajua enää että mikä on se opiskelijoiden maailma.

18:33

No sama pätee tässä tilanteessa. Jos me ei pystytä perässä siinä, että mitä on uusin teknologia, niin miten me voitaisiin opettaa kriittisiä viestintätaitoja ja ajattelutaitoja opiskelijoille? Eli siis mun sanoma olisi se, että meidän ei tarvitse haltioitua siitä uudesta teknologiasta, eikä etenkään

18:50

naivisti luottaa markkinointiin ja myyntipuheisiin siitä kaikesta, mitä se teknologia meille tarjoaa. Mutta sen

19:00

tähden niistä on tärkeä pysyä perillä, että me pystytään itse hyödyntämään niitä parhaalla mahdollisella tavalla ja pystytään tunnistamaan se, että missä tarvitaan kriittisyyttä tiedoissa ja taidoissa uuden teknologian suhteen. Eli se on kuin valtava apuväline valtava mahdollisuus, joka sisältää samalla myös suuria riskejä. Mutta meidän riskit pitää myös just pystyä käsittelemään suhtautumalla niihin teknologioihin kriittisesti.

19:27

Tommi: Miten

19:29

meidän kannattaisi lähestyä

19:32

opetusta ihan käytännön tasolla sitten ja minkälaista materiaalia meidän kannattaisi.

19:41

tuottaa ja opettaa sitten meidän kursseilla?

Tuukka: No mä palaan oikeastaan siihen peruspointtiin, minkä mä tuossa esitin. Koska kieli ja ajattelu kieli ja käsitteellinen ajattelu kulkee käsi kädessä, niin viestinnän opetus, kommunikaation opetus, kielten opetus on jo lähtökohtaisesti ajattelutaitojen opettamista, ja silloin kun siihen tuodaan mukaan mitä tahansa tämmöistä, analyyttistä tai kriittistä. Olipa se mediakritiikkiä tai tekstianalyysiä

20:13

tai mitä vaan, niin silloin se on jo kriittisen ajattelun opettamista keskeisellä tavalla. Ja sitten mä näen sen niin, että monet viestinnän opetuksen muodot ja sisällöt jo sellaisenaan toteuttaa kriittisen ajattelun opettamista mun näkökulmasta. Eli kun opetetaan toisten kuuntelemista, viestien tulkintaa, selkeää viestintää, harkittua viestien muodostamista, jäsentelyä, toisten kommunikaation analysointia,

20:44

kriittistä suhtautumista sekä omiin argumentteihin ja omiin tuotoksiin että toisten, niin kaikki tää on jo osa kriittisen ajattelun opettamista, jota ilman sitä kriittistä ajattelua ei voikaan ylipäätään opettaa. Ja

21:02

yksi tärkeä pointti on tietysti se, että pitää ylipäätään mielessään tämän ajattelun ja kielen välisen yhteyden. Ja sitten kuitenkin sen, että kriittisessä ajattelussa on tarkoitus että siinä otetaan tämmöinen kyseenalaistavan harkitseva (aluksi ainakin) skeptinen suhde sekä omiin uskomuksiin että toisten uskomuksiin. Että se on myös itsekritiikkiä. Eli suhtautuminen omien ajattelun tuotosten tai viestintätuotosten käsittelyyn kriittisesti, niin se on kriittisen ajattelun opettamista, koska kriittinen ajattelu ei tarkoita sitä, että me ollaan kriittisiä vain toisiaan kohtaan

21:37

tai että me ollaan jotenkin kielteisiä. Sitä se ei ole suinkaan, vaan se on punnittua, harkittua, tutkivaa ajattelua, jonka pitäisi suuntautua yksi lailla itsekriittisesti meidän omiin uskomuksiin kuin meille tarjolla oleviin uskomuksiin. Hyvien viestintätaitojen oppiminen liittyy kumpaankin suuntaan: että me pystytään analysoimaan kriittisesti omia uskomuksiaan ja käsityksiä, jos me pystytään tuottamaan ne hyvin.

22:09

Eli me saadaan selkeästi ilmaistua, että mitä me ajatellaan. Se on tietty ennakkoehto sille, että me pystytään suhtautumaan sen jälkeen siihen myös kyseenalaistavasti ja vastaavasti. Meidän pitää ensin ymmärtää toisten ihmisten viestintää, jotta me voidaan suhtautua siihen kriittisesti. Tästä se kaikki lähtee.

22:26

Mutta sitten voi tietysti ajatella, että on monia opetusmuotoja, joita voisi jotenkin pitää erityisesti kriittisen ajattelun kannalta hyödyllisinä. Tällaisia on mun mielestä esimerkiksi vaikka argumentaatioanalyysi, argumentaation opettaminen eri muodoissaan, argumentaatiota teoriat. Argumentaation opettaminen on hyvin lähellä kriittisen ajattelun opettamista ja monessa suhteessa ne on ihan yksi ja sama

22:56

asia. Yksi tämmöinen argumentaatiomuoto mitä mä olen itse pitänyt kiinnostavana

23:02

(kun tietysti aina joihinkin kiinnittää sitten enemmän huomiota kuin toisiin) on väittely opetusmenetelmä. Mä oon kirjoittanut kirjan väittelystä opetusmenetelmän ja mä pidän sitä hyvin toteutettuna erinomaisena kriittisen ajattelun opettamisen muotona, koska väittelyssä opitaan ottamaan nimenomaan tätä etäisyyttä omista vallitsevista käsityksistä ja mahdollisesti joudutaan puolustamaan semmoisia käsityksiä, mitä me ei ollenkaan kannateta. Eli ottamaan niinku nimenomaan skeptinen etäisyys siihen, että mitä ne uskomukset on

23:36

ja tutkitaan jotain aihetta perusteellisesti, valotetaan sitä puolin ja toisin. Eli monista näkökulmista puolesta ja vastaan ja pidättäydytään ottamasta lopullista kantaa, eli muotoilemista lopullista mielipidettä arvostelmia ennen kuin sitä asiaa on perusteellisesti tutkailtu. Väittely tarjoaa tähän erinomaisen mahdollisuuden ja sen takia mä oon ollut kiinnostunut nimenomaan siitä, mitenkä välttelyllä voidaan opettaa kriittistä ajattelua. Mulla on ollut pitkän aikaa monta vuotta Turun yliopiston oikeustieteellisen tiedekunnan kanssa

24:09

tällaisia yhteishankkeita missä on väittelyä käytetty opetuksessa ja se tuntuu sopivan juristeille ja juristiopiskelijoille erittäin hyvin lähestymistapana. Mutta se sopii mun mielestä ihan mihin tahansa opetukseen. Ja toki väittelyn käyttäminen on viestinnän opettajille tuttua,

24:27

mutta mä korostaisin siinä sitä, että väittelyä voi käyttää myös huonosti. Sen voi toteuttaa myös huonosti ja mä tarkoitan sillä sitä, että silloin siinä korostuisi kaikki tämmöinen kikkailu ja performanssi, toisten vedättäminen millä tahansa, niinku säpäkällä ilmaisukeinolla. Eli se olisi tämmöistä kiistatpuhetta, eristiikkaa. Sellaista retoriikkaa, missä vastuu siirtyy kuulijoille ja se ei sitten taas ole kriittisen ajattelun mukaista väittelyä.

24:58

Kriittisen ajattelun mukaisessa väittelyssä pitää aina korostua nimenomaan argumentaatio ja pyrkimys siihen, että ymmärretään sen väittelyn jälkeen se asia paremmin. Eli kriittinen ajattelu pyrkii kohti tietoa ja parempaa ymmärrystä. Eli siihen liittyy tämmöinen tietty tiedollisiin arvoihin ja jopa sosiaalisiin arvoihin moraaliin kuuluva puoli, että kriittistä ajattelua ei toteuteta siten, että me opetellaan huijaamaan toisia ihmisiä, vaikka sekin olisi viestinnällisesti mahdollista vaan

25:32

kriittinen ajattelu on sen tyyppistä viestinnän opettamista, missä aina korostuu tietosisällöt, argumentaatio ja sen taitavan taitava esittäminen, sen taitava kuunteleminen ja analyysi.

25:43

Ja aina korostuu pyrkimys kohti parempaa tietämystä ja parempaa ymmärrystä, ja jos just tän pitää mielessänsä, niin viestintäopinnot voi erittäin monenlaisin tavoin tukea kriittisen ajattelun oppimista.

26:01

Tommi: Mainiota. Käyttäkäämme siis voimiamme hyvään.

26:06

Siihen on hyvä lopettaa. Kiitos Tuukka!

26:09

Tuukka: Kiitos.

Interview with Tuukka Tomperi for 2digi2 Transcipt in English

Tommi Kakko: Tuukka Tomperi is a researcher at the Faculty of Education at the University of Tampere, a science journalist and a non-fiction writer. You kindly agreed to tell us language center teachers something about critical thinking. Before we do anything else, can you give us a definition of critical thinking?

Tuukka Tomperi: Yes, thank you, Tommi! It is very nice to participate in this and the topic is indeed broad and very important to me, very close in the sense that I am originally trained as a philosopher. I don’t really know what I would call myself nowadays, but I have been working in teacher education and educational sciences since the 2000s and teaching critical thinking and how teachers can teach critical thinking. So the pedagogical starting points for critical thinking teaching critical thinking and how teachers can teach critical thinking. So, the pedagogical starting points for teaching critical thinking are topics about which I have written and then taught. Let’s see if we can get some clarity on this broad topic during this conversation.

Of course, we can ask what critical thinking is, and often it is associated with rejection and negativity in everyday language and in the media. However, when we talk about critical thinking in science, philosophy, psychology and education, we refer to a certain kind of discretion and evaluative ability.

At its core, critical thinking involves questioning our beliefs, both our own and those presented by others. We question our worldview, our ideas, our values and examine them thoroughly so that we can consider whether we are right or wrong. The essence of critical thinking is that we refrain from forming an opinion or making a critical statement until we have examined the issue enough to form a more accurate picture of what we are thinking about. Only then do we form a critical view of the subject. There are many ways to define what critical thinking is, but one definition I have used a lot is from a philosopher called Matthew Lipman who defines a critical thinker as someone who thinks rationally in a way that is conducive to judgment, relies on criteria, is self-correcting and sensitive to context.

This is a bit complex, but all these basic elements must be included. That is, some common criteria must be applied when evaluating something and the context, the information content of the field, must be taken into account. Otherwise, critical thinking cannot succeed. If we do not know much about the subject, we must be able to correct our own ideas, and we must take into account that we may be wrong. All critical thinking always starts from this point, and then we try to develop our own ability to evaluate rationally.

Critical thinking is essentially investigative thinking that questions beliefs. It is questioning our own beliefs and those of others. Critical thinking involves questioning our worldview, our ideas and our values, and examining them thoroughly so that we can consider whether we are right or wrong.

Tommi: OK! What about language center teachers? What do we need to know about critical thinking?

If I think specifically about communication teaching and language teaching and the work of language center teachers, in my opinion, I can say right off the bat that these go hand in hand. So, you are already right at the heart of the matter. That is perhaps my main message: you don’t have to think about any strange newfangled tricks if you do your basic work well. It is a central part of teaching critical thinking to university students. All this of course starts with the fact that we know psychologically that all more advanced and higher-level thinking, all conceptual thinking, happens in language. It uses language and language and thinking go hand in hand when we try to think well about any substantial issues. It cannot be done without language.

A newer socio-constructivist psychology of learning (the term is not really important here) whose central pioneer was the Russian Lev Vygotsky brought to our awareness the fact that we humans learn high-level or conceptual thinking specifically by participating in communication. Children, for example, learn to think by listening to and participating in communication with other people. And gradually, they internalize the characteristics, means and skills that occur in communication into their own thinking, so that they can do it inside their heads (or wherever thinking takes place), all in silence without communication. But language and participation in a skillfully thinking and conversing language community is precisely the way we learn skillful thinking. In this sense, language skills are already the starting point for teaching critical thinking.

As an addition, in today’s world, if we think about what communication and critical thinking are today, to me, what is emphasized is that due to the characteristics of our current culture and society, critical thinking is increasingly media criticism, so we need more and more interpretive critical media skills and competencies without which we cannot achieve the kind of intellectual self-defense critical thinking is and is supposed to be.

We are currently living in a society or culture or world where we have more and better opportunities for knowledge-based thinking and communication than ever before in human history. But at the same time, it also includes a lot of noise, misinformation and disinformation, as you all know. All these problems are as broad as the opportunities that technology provides in communication, media and digital media. So, even if these opportunities for the development of a knowledge-based and skillfully thinking society are greater than ever, the same thing as before is true: that knowledge or information affects society, makes the world a better place or gives us the opportunity to improve the world only if that knowledge can be changed into such individual and collective knowledge that is somehow practical. And if we cannot use that information critically and skillfully with each other, then the amount of information and its availability will not help us in the end.

If you think about media criticism today, it is easy to see that there are many factors that are very challenging to our thinking. There is constantly too much information, more than we can digest on any topic. Every day is so full of material that we cannot keep up, even if we could imagine ourselves following everything. And then, because there is so much information, things are not connected. Thus, there is this kind of meaning gap that we fill on the basis of previous knowledge or previous prejudices, our own experiences or emotions or any of these easier methods. So, we cannot create enough links between things to fully understand them.

Well, then of course there is not enough time to think and stop to question all the news or all media content, all social media conversations we encounter. They flow like a formless flowing ribbon in front of our eyes. Ultimately, we can rarely focus on it or pause it, so we are constantly lacking in time. In addition, people’s memories are always limited, so even if we have learned many things over the years or decades, they tend to fade into the haze of memory, and we cannot recall them.

So, in this kind of extremely saturated and busy media environment, it is very difficult for beings like us whose psychological abilities have not changed much over tens of thousands of years to act. This brings us to the question that in such a society, one could think that the need for critical thinking is greater than ever precisely because we live in a communication environment that is full of all kinds of attempts to influence us.

But still, the main message to you as teachers of communication and language skills is precisely that when students are taught to communicate well, carefully, thoughtfully, in clearly structured forms, and then, correspondingly, also to read and listen well and carefully to the communication of others, these are already the core elements of current critical thinking. In this sense, I see teaching communication in all its forms as an essential part of teaching critical thinking without any further fancy twists and turns (which of course there also are and we can think about them too, but they are not essential).

Tommi: While digital overload can be a problem, it is important to remember that these tools can also be used to our advantage. One such approach is the use of artificial intelligence (AI) and other similar technologies. These tools can help us filter and analyze large amounts of data, making it easier to extract meaningful knowledge. Do you have any other insights into the use of digital tools as a solution instead of a problem? I’m thinking about the extended mind theory, for example.

Tuukka: It is a very important question in today’s world, and it is precisely as you said. From the perspective of the extended mind or even extended consciousness research, various tools have long been used for communication and memory, such as written text, images and all forms of printed expression. These have been extensions of our minds, especially in terms of expanding our memory, so that we do not have to memorize everything. For example, looking at a picture of a map can help us visualize a location in our minds, whether we look at it on paper or on a mobile phone.

The fact that these digital tools have developed so rapidly in recent decades has brought us a lot of new opportunities. It is clear to all of us today, including teachers, that they are the most important tools for our thinking and memory. But if I use the example of a map, it reminds me of how digital technology may also in some way narrow our thinking. By this I mean that if I think of a paper map and a map that is used today, for example, on a mobile phone, before when we used the map on paper, of course, if we were in a bad situation without good landmarks or street names, we still needed a compass. In addition, we had to position ourselves somehow on that map and learn to read it and the compass.

This required a demanding skill of recognizing the objects on the map. Well, the reading skills of maps for urban people like me today are based only on looking at street names and landmarks and then the direction.

During this era of digital technology, we can simply turn on the route indicator and then listen to the instructions or look at them and turn left, turn right, or go straight. We don’t even have to learn how to read the map.

As a result, we lose our understanding of where we are on the map. This is a good example of how these powerful technologies can also be harmful or narrow our thinking and limit our understanding. This risk exists in all these technologies, especially in the so-called artificial intelligence. We have all noticed that social media is full of enthusiasm about what can be achieved with these artificial intelligence programs or applications. Younger generations may forget that these are not actually intelligent at all. They are machine calculations based on certain algorithms and a certain amount of data that these algorithms filter, and then they produce some kind of responses or content for us based on prompts. So, they are not actually intelligent, nor do they think anything, which brings up the observation that the work and effort of thinking remains with us humans. The more this technology’s power increases, the more it becomes a black box.

What I mean is this. When we use a map application to navigate, we may only hear instructions to go here and there, and we may not know what is happening on the map. We do not know where we are on the map, and it is like a black box from which we only get output. The more technology is hidden from us, the more important it becomes to understand it better so that we can think critically with it and about it. These tools are absolutely effective. For example, the internet and its information content have been hugely liberating, because we only need a certain type of metadata for many things. If we know where to look for for detailed information, such as dates, names or other such things, we do not need to memorize it. But we still need that metadata. We still need a comprehensive understanding of a field, and we need to learn a lot about the content of the information in that field. Otherwise, we cannot use the internet effectively and, in the same way as any new technology, we should learn to understand how the technology works. This way, we can approach it critically and use it as an effective aid to our own thinking.

Now, if I think about how teachers face this new technology and, for example, this machine calculation or artificial intelligence technology, I myself think (and I always say this to teachers) that we must try to keep up with and follow the development of new technology to the extent that we understand what is happening and what these new technologies do and how they can be used. For example, at the moment, with how ChatGPT produces text, it is good to familiarize oneself with the principle, because it is a kind of guessing technology, a guessing machine, and there is no content there in itself that it could produce for us, so to speak. But it is good to know how it works so that we understand what is happening and so that we can also teach students to approach it critically and understand the risks involved. If we fall behind in technology, we will not notice the need for critical thinking or challenge students to approach new technology critically. If I may make an exaggerated point, I would think that if an old teacher who grew up in the oral tradition of the university suddenly encountered a situation where printing has become widespread and students can even buy books to read in their own time, then, if he did not understand the significance of this, he or she would fall behind and no longer understand what the students’ world is like.

The same applies in our situation: if we cannot keep up with the latest technology, how can we teach critical communication skills and thinking skills to students?

So, my message is that we should not be mesmerized by new technology and avoid trusting naively the marketing and sales pitches about everything that technology offers us. But it is important to stay on top of it so that we can use it ourselves in the best possible way and identify where critical thinking is needed in terms of knowledge and the skills related to new technology. It’s an important tool, a huge opportunity that also contains great risks. But we must be able to handle our risks by approaching these technologies critically.

Tommi: How should we approach teaching from a practical perspective? What kinds of materials should we produce and then teach on our courses?

Tuukka: Well, I will return to the basic point I made earlier: because language and thinking, language and processing thinking go hand in hand, teaching communication and language teaching are essentially teaching thinking skills, and when anything analytical or critical is brought into it, whether it’s media criticism or text analysis or anything else, then it’s already essentially teaching critical thinking.

I think that many forms of communication teaching already implement the teaching of critical thinking. That is, when we teach listening to others, interpreting messages, clear communication, thoughtful message formation, structuring communication with others, analysis, critical attitude towards one’s own arguments and those of others, all of this is already part of teaching critical thinking. You cannot teach critical thinking without these.

One important point to keep in mind is the connection between thinking and language. In critical thinking, the goal is to take a questioning and deliberative approach, and, initially at least, a skeptical attitude towards one’s own beliefs and those of others. It is also self-criticism. So, it is critical thinking to approach the products of one’s own thinking or communication critically, because critical thinking does not mean that we are critical of only others or that we have negative attitudes. It is thoughtful, deliberate, and investigative thinking that should be directed in the same way self-critically towards our own beliefs as towards the beliefs presented to us. Good communication and learning communication skills go both ways, so that we can analyze our own beliefs and understand the communication of others critically.

So, clearly expressing what we think is a prerequisite for being able to approach what has been expressed critically afterwards. Similarly, we must first understand the communication of other people in order to be able to approach it critically. That’s where it all starts.

But then one can of course think that there are many teaching methods that could be considered particularly useful for critical thinking. Such methods include argument analysis, teaching argumentation in its various forms, argumentation theories and teaching argumentation, and they are very close to teaching critical thinking and in many respects they are one and the same.

One such method is debate as a teaching method. I have written a book on debate as a teaching method, and I consider it, when implemented well, an excellent way of teaching critical thinking, because in debate, one learns to take this distance from one’s prevailing beliefs, and one may have to defend beliefs that one does not support at all. That is, to take this skeptical distance to what those beliefs are.

When we examine a topic thoroughly, we take a variety of perspectives for and against and refrain from taking a final stance. We formulate our final opinion and criticism only after thoroughly examining the issue. Debate provides an excellent opportunity for this. That’s why I’ve been interested in how debate can be used to teach critical thinking, and I’ve had several joint projects with the Faculty of Law at the University of Turku for many years. These joint projects have used debate in teaching, and it seems to be a very good approach for law students. But I think it’s suitable for any kind of teaching. And, of course, it’s familiar to many of you as teachers.

However, I would emphasize that debate can also be used poorly. It can be executed poorly, and by this I mean that all this trickery and performance, using any means to deceive others, would be emphasized. It would be this kind of dispute, eristic rhetoric, where the responsibility shifts to the listeners. That is not debate that follows critical thinking.

In a debate that follows critical thinking, the emphasis should always be on argumentation and the aim of understanding the matter better after the debate. Critical thinking aims towards knowledge and better understanding. It includes a certain aspect related to cognitive values and even social values and morality. That is, critical thinking is not implemented by learning to deceive others.

Even though it is possible to deceive others through communication, critical thinking involves a type of education where the emphasis is always on content, argumentation and its skillful presentation, skillful listening and analysis.

And the aim is always towards better knowledge and better understanding, and one should always keep this in mind. So, basic communication studies can support learning critical thinking in many ways.

Tommi: Excellent! Let’s use our powers for good. That’s a good place to end. Thank you Tuukka!

Tuukka: Thank you!

Argumentation is an important part of critical thinking skills in general, but there is no need to create a universal approaches to teaching argumentation at language centers. However, we offer some recommendations for resources and an example of assignment below to inspire teachers and stimulate the imagination.

There are many branches of argumentation theory, but here we focus on the types of argumentation used in an academic setting. The resources below, we believe, provide a good introduction to argumentation; the example assignment is one that could be used on an English course on academic writing.

Resources

Stephen Toulmin’s The Uses of Argument (2nd ed., 2003) is a classic study of practical arguments or informal logic (as opposed to arguments in formal logic). Its most famous contribution to argumentation theory is the Toulmin model.

David Zarefsky’s The Practice of Argumentation: Effective Reasoning in Communication (2019) is a practical guide to analyzing and composing arguments. It includes exercises and can be used as a textbook.

Chaïm Perelman and L. Olbrechts-Tyteca’s The New Rhetoric: A Treatise on Argumentation (1973) considers, among numerous other things, different kinds of audiences and questions related to values. The original French title, Traité de l’argumentation: La nouvelle rhétorique, was published in 1958.

Frans H. van Eemeren and Rob Grootendorst‘s A Systematic Theory of Argumentation: The Pragma-Dialectical Approach (2003) is an overview of the pragma-dialectical approach to argumentative discourse developed by van Eemeren and Grootendorst.

Links

Many universities around the world have excellent pages dedicated to argumentation. For example, Purdue University OWL‘s Toulmin Model page explains how the model works very clearly.

The New York Times has a list of 300 Questions and Images to Inspire Argument Writing that is useful for teachers looking for topics.

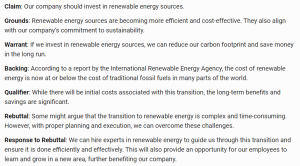

AI prompts are a quick and easy way to create examples of arguments for teaching. For example,

Write a business-related example argument that includes the parts of argument listed in the Toulmin model

outputs the following response on Bing:

Send in your suggestions! We would love to update the list with more useful online resources.

Example assignment

Note: This type of assignment works on an English academic writing course. It is only concerned with drafting an argument and produce a first draft. I.e., it will not help the student to produce a finished essay.

Write a short essay of 600–800 words. You are expected to compose an argument following the instructions. Make sure your argument can be made to fit the word limit. Writing a concise essay is not always easy.

Below is an illustration of what roughly 800 words look like, arranged into three sections: introduction, body, conclusion. The word count includes the name of the author and a reference to a source.

Following one model of the writing process, we can follow four steps when planning the essay: prewriting, drafting, revising and editing. Here, we are concerned with the first two.

First (prewriting), you need to decide on a topic and find relevant sources. Then, we can proceed by drafting an argument. Your argument may be a counterargument that includes a critical claim related to the sources or you can use your sources to compose an original argument; you may, for example, compare arguments in two or more sources.

To draft the argument, we can use the Toulmin Model. The Toulmin Model is a simple way of organizing the parts of an argument into a schematic such as the one below. Moreover, it introduces several terms that you will find useful for both argument analysis and composition.

Your argument should include

- a claim: an assertion you want to prove to your audience

- data: the evidence or grounds for your claim

- a warrant: reasoning that allows the leap from the data to the claim

You may also want to include

- backing for the warrant: a justification for the warrant

- a rebuttal: a possible objection or exception against the claim

- a qualifier: a that limits the scope of the claim, such as a probability

The claim is the most important part of your argument. There are many types of claims. For example, there are claims of

- fact: something is or is not the case

- definition: a concept should be defined in a certain way

- value: A is better, more important or valuable than B

- policy: a course of action must or must not be taken

- cause: X caused or did not cause Y

Depending on your case, you may want to choose different types of claims. Note, for example, that should you compare the arguments in two or more sources (see above), this would be a claim of value.

Note also that the various parts of the argument can be mapped onto or emphasized at various sections of the paper. For example, you claim should be stated in the introduction and repeated in the conclusion. The data, warrant and backing will most likely find a home in the body of the essay. Rebuttals that explain the reason for the qualifier are probably best left to the latter parts of the essay; the conclusion or a discussion section, should you have one, would be an excellent place for it.

Good luck!